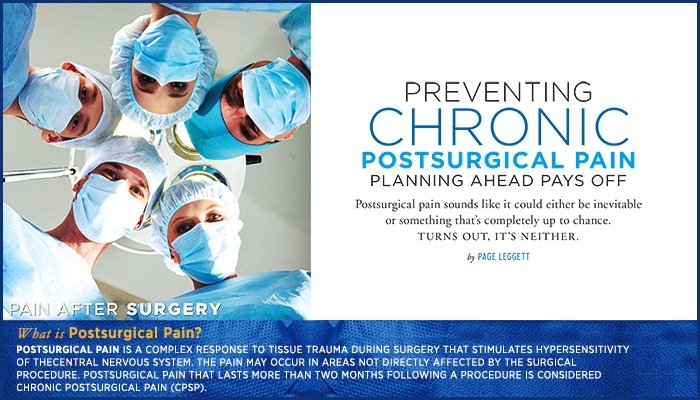

Chronic Postsurgical Pain

And, depending on the type of surgery, patients can play an important part in determining the duration and level of pain they experience after a procedure.

Debi McCutcheon, MD, a board-certified anesthesiologist and pain specialist who completed two pain fellowships at Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center, can speak to postsurgical pain from both a patient’s and physician’s perspective. When she had knee surgery in 2011, she was given what’s commonly known as a nerve block to reduce pain. (Physicians also refer to it as a “regional” technique.) It worked: she was pain-free for 26 hours after surgery —and it’s the first 24 to 48 hours after surgery when pain is likely to be greatest. “By the time my block wore off, I had started pain medication by mouth and was therefore able to stay ahead of the pain,” Dr. McCutcheon says.

Nerve blocks prevent pain signals from being transmitted to the brain. Epidurals are a common type of nerve block used to prevent labor pain.

It wasn’t physician privilege that allowed Dr. McCutcheon to have a nerve block; as an educated patient, she asked for it. Dr. McCutcheon believes all patients should ask their surgeons if such relief is available and appropriate for theirspecific surgery. Acute postsurgical pain is a possibility after any procedure. “Postsurgical pain is the body’s response to trauma resulting from intervention,” explains the More-head City, North Carolina-based Dr. McCutcheon.

WHAT CAUSES POST-OP PAIN?

Postsurgical pain can be a result of incision, pressure or distention. It’s more likely to occur when a nerve is stretched or severed. Strangely, the pain may not be felt at the site of the procedure. For example, if a patient undergoes an abdominal laparoscopic procedure, he may experience shoulder pain. “That’s because of shared pain pathways along the spinal column,” explains Dr. McCutcheon.

CHRONIC PAIN PATIENTS MUST TAKE EXTRA PRECAUTIONS

Anyone having a medical procedure — whether it involves an incision or not — should discuss the issue of pain management with the surgeon (and, if applicable, the anesthesiologist) in advance. However, people who already live with chronic pain are at greater risk of experiencing post-surgical pain. “The largest risk factor of post-op pain is the presence of pre-operative pain,” Dr. McCutcheon says.

“[Patients with chronic pain] should inform those taking care of them about their medications, including prescription, over-the-counter and herbal supplements used to treat their baseline pain,” says Dr. McCutcheon. “They should honestly disclose any use of alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs, as these factors may significantly affect their pain control.”

When a patient currently under the care of a pain physician is scheduled for a surgical procedure, he or she should ask the pain doc to help develop a plan. “I have several patients I see now who have recently scheduled surgery,” says Dr. McCutcheon. “I write up a suggested plan for them to share with the surgeon that includes strategies and appropriate medications.

“Patients should ask questions about what to expect in terms of pain after surgery and discuss any concerns they have,” she continues. “While the type of surgery will affect how long they should expect significant postoperative pain, they should, on average, expect only several weeks of significant post-op pain.”

Ben Musgrave, aged 54, says he experienced intense post-surgical pain — for a lot longer than a few weeks. In 2005,he was diagnosed with a desmoid tumor, a benign tumor that typically forms in the body’s connective tissue.

The tumor caused “only a twinge of pain,” says Musgrave, but he felt an “intense, stabbing pain almost immediately after surgery.” He called it a 10 on a scale of 1 to 10. After living with this pain for nearly a year, he consulted his family physician, who referred him to a pain specialist. “We tried different pain medications and a TENS (transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation) unit,” Musgrave says.

He experienced varying degrees of success with each treatment during the year he and his doctors searched for the right combination to work for him. Finally, doctors implanted a spinal cord stimulator. “The implant has been very helpful, and my pain today is, at times, almost zero,” Musgrave says.

THE PATIENT’S ROLE

Postsurgical pain need not be as common as it is. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), there were about 51 million inpatient procedures performed in the United States in 2010. And despite new treatment standards and educational efforts, acute postoperative pain continues to be undertreated, with up to 75 percent of Americans failing to get adequate post-op pain relief, according to Dr. McCutcheon.

It may seem counterintuitive, but alleviating or minimizing post-op pain starts well before surgery.

“It takes a certain amount of strategizing” to minimize the risk and severity of postsurgical pain, says Dr. McCutcheon. She says there was a time — and not that long ago — when the prevailing wisdom was that “huge amounts of narcotics were the way to treat pain” after surgery. Doctors know now there’s a better way.

“Communication between patient and doctor is necessary, even critical,” she says. And too often, it doesn’t happen. She doesn’t blame surgeons.

“They’re not necessarily trained in pain,” she says. “A recently trained surgeon is more likely to be open to alter-native ways of thinking about pain management. An old-school surgeon may just reach for the tried-and-true morphine.”

One solution, she believes, is involving an anesthesiologist in the planning stages. “I hope we get to the point that surgeons aren’t just asking postoperatively, ‘Did I fix the problem?’ but are also asking, ‘What’s your level of pain?’“

A surgeon may look at a post-op X-ray and say he or she corrected the problem,” she continues. “That may be true, but a patient doesn’t care if the problem was fixed if the pain lingers.”

FROM ACUTE TO CHRONIC PAIN…WHY ME?

While a certain level of acute pain may be expected after surgical procedures, pain that lingers is considered chronic, and a new course of action is required.“Chronic pain after surgery is typically defined as pain that lasts for more than two months without any other discernible cause,” says Dr. McCutcheon, who specializes in both chronic and acute pain. She says it’s important for patients to let their surgeons know if they have lingering pain beyond the two-month mark. They may need to see a pain specialist at that point.

Musgrave, who lived with postsurgical pain for a year, agrees. “Don’t suffer in silence,” he says. “To others with postsurgical pain, I advise them to seek help — because there is help out there.”

“Why some patients, and not others, experience chronic postsurgical pain (CPSP) is the question,” says Dr. McCutcheon. “Any surgical incision will result in tissue damage and activation of pain pathways. The problem is that in patients who experience CPSP, these pathways, once activated, remain activated and do not deactivate as they should.”

Doctors call the condition “central sensitization.” It can happen when the nervous system stays on constant high alert. The result is pain that remains even after the initial injury is healed. She says, “It’s a painful input that just keeps firing. It creates super-sensitive tissue around the incision.”Doctors aren’t sure why, but postsurgical pain is more common in young adults than in elderly patients and children. Some people may be genetically predisposed to CPSP.

Certain procedures have a higher incidence of CPSP. “Any traumatic injury can lead to chronic postsurgical pain, however surgeries that involve severing, retracting or stretching nerves are associated with higher incidence of developing CPSP,” says Dr. McCutcheon.

For instance, according to one study, Caesarean sections and dental surgeries have fairly low incidences of resulting in chronic postsurgical pain; respectively, they’re at 12 percent and between 5 and 13 percent. By contrast, CPSP resulting from amputations occurs in between 30 and 85 percent of all cases. Between 13 percent and 38 percent of patients who have breast augmentation will suffer from CPSP. For a mastectomy, that figure can vary from 11 percent to 57 percent.

A NEW APPROACH AND NEW (AND EFFECTIVE!) MEDICATIONS

Dr. McCutcheon is encouraged by the medical community’s relatively recent acceptance of pain as an important consideration. “Pain is now considered the fifth vital sign,”she says. “That’s as it should be. It used to be that you got your surgery, a pain pump, some pills and you went home,” she says. “But in the past five to ten years, doctors have begun to look at quality measures. Pain management has taken a step forward into the limelight as an important part of patient care.”

Encouragingly, she says, the medical community is also moving to a distinctly preventative approach. That’s not just Dr. McCutcheon’s hunch; it’s the official word from the practice guidelines for “Acute Pain Management in the Perioperative Setting,” an update by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Task Force on Acute Pain Management. It reads, in part:

• Whenever possible, anesthesiologists should use multimodal pain management therapy.

• Regional anesthesia with local anesthetics should be considered when appropriate.

Dr. McCutcheon says ASA recommendations for chronic pain include what doctors call “a multimodal pain regimen,” including “medications like gabapentin or Lyrica and NSAIDs such as ibuprofen or acetaminophen.”

Yes, that’s right. The tried-and-true Tylenol can reduce the need for narcotics in postsurgical patients by as much as50 percent, says Dr. McCutcheon.

The use of intravenous (IV) acetaminophen (Tylenol) is relatively new in the United States. “This has been a welcome addition to the postoperative pain regimen, especially in patients who are unable to take medications by mouth postoperatively,” Dr. McCutcheon says. “Utilizing acetaminophen as opposed to ibuprofen or similar drugs helps avoid gastrointestinal and renal complications that can be a concern in some patients.”

IV Tylenol should be scheduled for the first 48 hours after an operation. (Again, plan ahead!) The use of IV acetaminophen is more effective than oral dosing because of the ability of the medication to reach the bloodstream faster and stay at an effective dose longer.

Kimberly-Clark’s ON-Q Pump is another breakthrough. The pump, which is attached to a catheter placed just under the skin, “holds a local anesthetic which infuses through a peripheral nerve block catheter providing patients with three to five days of postoperative anesthesia,” explains Dr. McCutcheon. A patient can have it easily inserted after surgery and go home with it. “These are disposable and simple to use. A patient with no medical training can easily remove the device when it is appropriate. By extending the length of time the surgical area can be numb, patients’ overall post-operative pain can be greatly reduced.”

The time to consider postsurgical pain is before surgery. If your surgeon doesn’t mention a nerve block, ask if it’s appropriate for your condition and procedure. “The use of regional anesthesia, when appropriate, can make a significant difference in patient comfort in the immediate postoperative period,” says Dr. McCutcheon. “Use of this technique has also been associated with reduced risk for development of chronic postsurgical pain.”

In surgery, as in life, it pays to be prepared. {PP}

PainPathways Magazine

PainPathways is the first, only and ultimate pain magazine. First published in spring 2008, PainPathways is the culmination of the vision of Richard L. Rauck, MD, to provide a shared resource for people living with and caring for others in pain. This quarterly resource not only provides in-depth information on current treatments, therapies and research studies but also connects people who live with pain, both personally and professionally.

View All By PainPathways